СОДЕРЖАНИЕ

- 1 IELTS Тест PDF

- 2 Пробные тесты IELTS онлайн

- 3 IELTS practice tests

- 4 IELTS Academic Reading Test 3. Section 2

- 5 IELTS Reading Practice Test 3

- 6 IELTS Reading Practice Test 3-2

- 7 IELTS Simulation Test With Answers Volume 2

- 8 Share this test

- 9 Are you sure you want to exit?

- 10 Are you sure you want to view the solution now?

- 11 Review your answers

- 12 Time is up

- 13 Are you sure you want to submit?

- 14 READING PASSAGE 1

- 15 How to run a… Publisher and author Dav >

- 16 READING PASSAGE 2

- 17 Stadium Australia

- 18 READING PASSAGE 3

- 19 A Theory of Shopping

- 20 Ielts reading test 3-2

- 21 The headline of the passage: Autumn Leaves

- 22 IELTS Academic Reading test 2 Section 3

- 23 The dawn of culture

IELTS Тест PDF

Если вы хотите потренироваться перед экзаменом и вам нужен IELTS тест, то вот он, ждёт вас здесь (см.файлы ниже).

Если вы только начинаете подготовку и не знаете свой уровень и какой балл по IELTS можете получить прямо сейчас, этот тест тоже вас ждёт.

Выполнив эти задания вы прочувствуете формат экзамена и узнаете сколько у вас правильных ответов, т.е сможете посмотреть какой у вас балл.

Это Официальный IELTS тест от Cambridge!

Эффективнее всего выполнять тест так:

- Listening — 30 мин + 10 мин переписать ответы в экзаменационный бланк

- Reading—60 мин

- Writing — 60 минут / 2 задания

ПРОВЕРЯЙТЕ ПОТОМ СВОИ ОТВЕТЫ!

Важно, чтобы ваш writing проверил спец по IELTS!

Если сдаёте IELTS на бумаге, то лучше распечатать тест и сделать всё как на экзамене — на бумаге. Если сдаёте на компьютере (Computer-based IELTS), то делать тест нужно на компьютере, чтобы привыкнуть к формату и знать что там к чему. На сайтах официальных источников есть пробные задания.

Listening Test Recordings — Скачать (.pdf) (Записи в архиве .rar)

Пробные тесты IELTS онлайн

IELTS practice tests

| Practice Test 1 | |||

|

|

|

|

| Section 1 | Section 1 | Writing Task | Speaking Task |

| Section 2 | Section 2 | ||

| Section 3 | Section 3 | ||

| Section 4 | |||

ЭФФЕКТИВНЫХ ВАМ ТРЕНИРОВОК И БОЛЬШЕ БАЛЛОВ!

Поделиться или сохранить себе

IELTS Academic Reading Test 3. Section 2

This is section 2 of IELTS Reading test. Read the text below and answer the questions. After you finish, click ‘check’ and move on to the next section.

READING PASSAGE 2

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 15–30, which are based on Reading Passage 2 below.

The science of sleep

We spend a third of our lives doing it. Napoleon, Florence Nightingale and Margaret Thatcher got by on four hours a night. Thomas Edison claimed it was waste of time.

So why do we sleep? This is a question that has baffled scientists for centuries and the answer is, no one is really sure. Some believe that sleep gives the body a chance to recuperate from the day’s activities but in reality, the amount of energy saved by sleeping for even eight hours is miniscule — about 50 kCal, the same amount of energy in a piece of toast.

With continued lack of sufficient sleep, the part of the brain that controls language, memory, planning and sense of time is severely affected, practically shutting down. In fact, 17 hours of sustained wakefulness leads to a decrease in performance equivalent to a blood alcohol level of 0.05% (two glasses of wine). This is the legal drink driving limit in the UK.

Research also shows that sleep-deprived individuals often have difficulty in responding to rapidly changing situations and making rational judgements. In real life situations, the consequences are grave and lack of sleep is said to have been be a contributory factor to a number of international disasters such as Exxon Valdez, Chernobyl, Three Mile Island and the Challenger shuttle explosion.

Sleep deprivation not only has a major impact on cognitive functioning but also on emotional and physical health. Disorders such as sleep apnoea which result in excessive daytime sleepiness have been linked to stress and high blood pressure. Research has also suggested that sleep loss may increase the risk of obesity because chemicals and hormones that play a key role in controlling appetite and weight gain are released during sleep.

What happens when we sleep?

What happens every time we get a bit of shut eye? Sleep occurs in a recurring cycle of 90 to 110 minutes and is divided into two categories: non-REM (which is further split into four stages) and REM sleep.

Non-REM sleep

Stage one: Light Sleep

During the first stage of sleep, we’re half awake and half asleep. Our muscle activity slows down and slight twitching may occur. This is a period of light sleep, meaning we can be awakened easily at this stage.

Stage two: True Sleep

Within ten minutes of light sleep, we enter stage two, which lasts around 20 minutes. The breathing pattern and heart rate start to slow down. This period accounts for the largest part of human sleep.

Stages three and four: Deep Sleep

During stage three, the brain begins to produce delta waves, a type of wave that is large (high amplitude) and slow (low frequency). Breathing and heart rate are at their lowest levels.

Stage four is characterised by rhythmic breathing and limited muscle activity. If we are awakened during deep sleep we do not adjust immediately and often feel groggy and disoriented for several minutes after waking up. Some children experience bed-wetting, night terrors, or sleepwalking during this stage.

REM sleep

The first rapid eye movement (REM) period usually begins about 70 to 90 minutes after we fall asleep. We have around three to five REM episodes a night.

Although we are not conscious, the brain is very active — often more so than when we are awake. This is the period when most dreams occur. Our eyes dart around (hence the name), our breathing rate and blood pressure rise. However, our bodies are effectively paralysed, said to be nature’s way of preventing us from acting out our dreams.

After REM sleep, the whole cycle begins again.

How much sleep is required?

There is no set amount of time that everyone needs to sleep, since it varies from person to person. Results from the sleep profiler indicate that people like to sleep anywhere between 5 and 11 hours, with the average being 7.75 hours.

Jim Horne from Loughborough University’s Sleep Research Centre has a simple answer though: «The amount of sleep we require is what we need not to be sleepy in the daytime.»

Even animals require varied amounts of sleep:

Species

Average total sleep time per day

IELTS Reading Practice Test 3

An examination of the functioning of the senses in cetaceans, the

group of mammals comprising whales, dolphins and porpoises

Some of the senses that we and other terrestrial mammals take for granted are either reduced or absent in cetaceans or fail to function well in water. For example, it appears from their brain structure that toothed species are unable to smell. Baleen species, on the other hand, appear to have some related brain structures but it is not known whether these are functional. It has been speculated that, as the blowholes evolved and migrated to the top of the head, the neural pathways serving sense of smell may have been nearly all sacrificed. Similarly, although at least some cetaceans have taste buds, the nerves serving these have degenerated or are rudimentary.

The sense of touch has sometimes been described as weak too, but this view is probably mistaken. Trainers of captive dolphins and small whales often remark on their animals’ responsiveness to being touched or rubbed, and both captive and free ranging cetacean individuals of all species (particularly adults and calves, or members of the same subgroup) appear to make frequent contact. This contact may help to maintain order within a group, and stroking or touching are part of the courtship ritual in most species. The area around the blowhole is also particularly sensitive and captive animals often object strongly to being touched there.

The sense of vision is developed to different degrees in different species. Baleen species studied at close quarters underwater – specifically a grey whale calf in captivity for a year, and free-ranging right whales and humpback whales studied and filmed off Argentina and Hawaii – have obviously tracked objects with vision underwater, and they can apparently see moderately well both in water and in air. However, the position of the eyes so restricts the field of vision in baleen whales that they probably do not have stereoscopic vision.

On the other hand, the position of the eyes in most dolphins and porpoises suggests that they have stereoscopic vision forward and downward. Eye position in freshwater dolphins, which often swim on their side or upside down while feeding, suggests that what vision they have is stereoscopic forward and upward. By comparison, the bottlenose dolphin has extremely keen vision in water. Judging from the way it watches and tracks airborne flying fish, it can apparently see fairly well through the air–water interface as well. And although preliminary experimental evidence suggests that their in-air vision is poor, the accuracy with which dolphins leap high to take small fish out of a trainer’s hand provides anecdotal evidence to the contrary.

Such variation can no doubt be explained with reference to the habitats in which individual species have developed. For example, vision is obviously more useful to species inhabiting clear open waters than to those living in turbid rivers and flooded plains. The South American boutu and Chinese beiji, for instance, appear to have very limited vision, and the Indian susus are blind, their eyes reduced to slits that probably allow them to sense only the direction and intensity of light.

Although the senses of taste and smell appear to have deteriorated, and vision in water appears to be uncertain, such weaknesses are more than compensated for by cetaceans’ well-developed acoustic sense. Most species are highly vocal, although they vary in the range of sounds they produce, and many forage for food using echolocation. Large baleen whales primarily use the lower frequencies and are often limited in their repertoire. Notable exceptions are the nearly song-like choruses of bowhead whales in summer and the complex, haunting utterances of the humpback whales. Toothed species in general employ more of the frequency spectrum, and produce a wider variety of sounds, than baleen species (though the sperm whale apparently produces a monotonous series of high-energy clicks and little else). Some of the more complicated sounds are clearly communicative, although what role they may play in the social life and ‘culture’ of cetaceans has been more the subject of wild speculation than of solid science.

Questions 15-21

Complete the table below.

Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from Reading Passage 2 for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 15–21 on your answer sheet.

| SENSE | SPECIES | ABILITY | COMMENTS |

| Smell | toothed | no | Evidence from brain structure |

| Baleen | not certain | related brain structures are present | |

| Taste | Some types | Poor | Nerves linked to their 15 are underdeveloped |

| Touch | all | yes | region around the blowhole very sensitive |

| Vision | 16 | yes | probably do not have stereoscopic vision |

| doplhins, porpoises | yes | probably have stereoscopic vision 17 | |

| 18 | yes | probably have stereoscopic vision forward and upward | |

| bottlenose dolphin | yes | exceptional in 19 and good in air-water interface | |

| boutu and beiji | poor | have limited vision | |

| Indian susu | no | probably only sense direction and intensity of light | |

| Hearing | most large baleen | yes | usually use 20 repertoire limited |

| 21 whales | yes | song-like | |

| toothed | yes | use more of frequency spectrum; have wider repertoire |

Questions 22-26

Answer the questions below using NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 22–26 on your answer sheet.

22 Which of the senses is described here as being involved in mating?

23 Which species swims ups />

24 What can bottlenose dolphins follow from under the water?

25 Which type of habitat is related to good visual ability?

26 Which of the senses is best developed in cetaceans?

IELTS Reading Practice Test 3-2

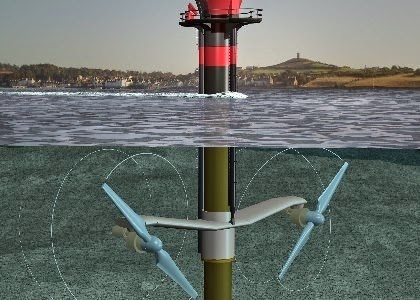

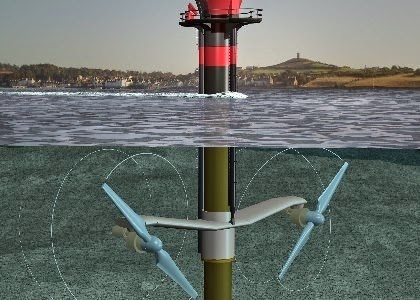

T > Undersea turbines which produce electricity from the tides are set to become an important source of renewable energy for Dritain. lt is still too early to predict the extent of the impact they may have. but all the signs are that they will play a significant role in the future.

Operating on the same principle as wind turbines, the power in sea turbines comes from tidal currents which turn blades similar to ships’ propellers, but. unlike wind, the tides are predictable and the power input is constant. The technology raises the prospect of Britain becoming self-sufficient in renewable energy and drastically reducing its carbon dioxide emissions.

If tide, wind and wave power are all developed. Britain would be able to close gas, coal and nuclear power plants and export renewable power to other parts of Europe. Unlike wind power which Britain originally developed and than abandoned for 20 years allowing the Dutch to make it a major industry. undersea turbines could become a big export earner to island nations such as Japan and New Zealand.

Work on designs for the new turbine blades and sites are well advanced at the University of Southampton‘s sustainable energy research group. The first station is expected to be installed off Lynmouth in Devon shortly to test the technology in a venture jointly funded by the department of Trade and Industry and the European Union. AbuBakr Bahaj, in charge of the Southampton research. said: The prospects for energy from tidal currents are far better than from wind because the flows of water are predictable and constant.

The technology for dealing with the hostile saline environment under the sea has been developed in the North Sea oil industry and much is already known about turbine blade design, because of wind power and ship propellers. There are a few technical difficulties, but I believe in the next live to ten years we will be installing commercial marine turbine farms.’ Southampton has been awarded £2’l5.U.`D over three years to develop the turbines and is working with Marine Current Turbines. a subsidiary of IT power; on the Lynmouth project. EU research has now identified 1GB potential sites for tidal powen BG% round the coasts ol Britain. The best sites are between islands or around heavily indented coasts where there are strong tidal currents.

Our new home -preparation book — — How Not To Fear IELTS Writing — cracked the most effective shortcut techniques of IELTS writing preparation that many students had been struggling for years to find. Click here for free download .

IELTS Simulation Test With Answers Volume 2

Reading Practice Test 3

Are you sure you want to exit?

Are you sure you want to view the solution now?

*This action will NOT submit your test and your answers will be LOST

Review your answers

Time is up

Please choose the following option

Are you sure you want to submit?

READING PASSAGE 1

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 1-13 which are based on Reading Passage

A

Prior to the Second World War, all the management books ever written could be comfortably stacked on a couple of shelves. Today, you would need a size able library, with plenty of room for expansion, to house them. The last few decades have seen the stream of new titles swell into a flood. In 1975, 771 business books were published. By 2000, the total for the year had risen to 3,203, and the trend continues.

B

The growth in pubishing activity has followed the rise and rise of management to the point where it constitutes a mini-industry in its own right. In the USA alone, the book market is worth over $lbn. Management consultancies, professional bodies and business schools were part of this new phenomenon, all sharing at least one common need: to get into print. Nor were they the only aspiring authors. Inside stories by and about business leaders balanced the more straight-laced textbooks by academics. How-to books by practising managers and business writers appeared on everything from making a presentation to developing a business strategy. With this upsurge in output, it is not really surprising that the quality is uneven.

C

Few people are probably in a better position to evaluate the management canon than Carol Kennedy, a business journalist and author of Guide to the Management Gurus, an overview of the world’s most influential management thinkers and their works. She is also the books editor of The Director. Of course, it is normally the best of the bunch that are reviewed in the pages of The Director. But from time to time, Kennedy is moved to use The Director’s precious column inches to warn readers off certain books. Her recent review of The Leader’s Edge summed up her irritation with authors who over-promise and under-deliver. The banality of the treatment of core competencies for leaders, including the ‘competency of paying attention’, was a conceit too far in the context of a leaden text. ‘Somewhere in this book,’ she wrote,‘there may be an idea worth reading and taking note of, but my own competency of paying attention ran out on page 31.’ Her opinion of a good proportion of the other books that never make it to the review pages is even more terse.‘Unreadable’ is her verdict.

D

Simon Caulkin, contributing editor of the Observer’s management page and former editor of Management Today, has formed a similar opinion. A lot is pretty depressing, unimpressive stuff.’ Caulkin is philosophical about the inevitability of finding so much dross. Business books, he says,‘range from total drivel to the ambitious stuff. Although the confusing thing is that the really ambitious stuff can sometimes be drivel.’ Which leaves the question open as to why the subject of management is such a literary wasteland. There are some possible explanations.

E

Despite the attempts of Frederick Taylor, the early twentieth-century founder of scientific management, to establish a solid, rule-based foundation for the practice, management has come to be seen as just as much an art as a science. Once psychologists like Abraham Maslow, behaviouralists and social anthropologists persuaded business to look at management from a human perspective, the topic became more multidimensional and complex. Add to that the requirement for management to reflect the changing demands of the times, the impact of information technology and other factors, and it is easy to understand why management is in a permanent state of confusion. There is a constant requirement for reinterpretation, innovation and creative thinking: Caulkin’s ambitious stuff. For their part, publishers continue to dream about finding the next big management idea, a topic given an airing in Kennedy’s book. The Next Big Idea.

F

Indirectly, it tracks one of the phenomena of the past 20 years or so: the management blockbusters which work wonders for publishers’ profits and transform authors’ careers. Peters and Waterman’s In Search of Excellence: Lessons from America’s Best-Run Companies achieved spectacular success. So did Michael Hammer and James Champy’s book. Reengineering the Corporation: A Manifesto for Business Revolution. Yet the early euphoria with which such books are greeted tends to wear off as the basis for the claims starts to look less than solid. In the case of In Search of Excellence, it was the rapid reversal of fortunes that turned several of the exemplar companies into basket cases. For Hammer’s and Champy’s readers, disillusion dawned with the realisation that their slash-and-burn prescription for reviving corporate fortunes caused more problems than it solved.

G

Yet one of the virtues of these books is that they could be understood.There is a whole class of management texts that fail this basic test.‘Some management books are stuffed with jargon,’ says Kennedy.‘Consultants are among the worst offenders.’ She believes there is a simple reason for this flight from plain English.’They all use this jargon because they can’t think clearly. It disguises the paucity of thought.’

H

By contrast, the management thinkers who have stood the test of time articulate their ideas in plain English. Peter Drucker, widely regarded as the doyen of management thinkers, has written a steady stream of influential books over half a century. ‘Drucker writes beautiful, dear prose.’ says Kennedy, ‘and his thoughts come through.’ He is among the handful of writers whose work, she believes, transcends the specific interests of the management community. Caulkin also agrees that Drucker reaches out to a wider readership. ‘What you get is a sense of the larger cultural background,’ he says.‘That’s what you miss in so much management writing.’ Charles Handy, perhaps the most successful UK business writer to command an international audience, is another rare example of a writer with a message for the wider world.

READING PASSAGE 2

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 14-26 which are based on Reading Passage 2.

Stadium Australia

A

You might ask, why be concerned about the architecture of a stadium? Surely, as Long as die action is entertaining and the building is safe and reasonably comfortable, why should the aesthetics matter’ This one question has dominated my professional life, and its answer is one 1 find myself continually rehearsing. If one accepts that sporting endeavour is as important an outlet for human expression as, say, the theatre or cinema, fine art or music, why shouldn’t the buildings in which we celebrate this outlet he as grand and as inspirational as those we would expect, and demand, in those other areas of cultural life? Indeed, one could argue that because stadiums are, in many instances, far more popular than theatres or art galleries, we should actually devote more, and nor less, attention to their form. Stadiums have frequently been referred to as ‘cathedrals’. Football has often been dubbed ‘the opera of the people’. What better way, therefore, to raise the general public’s awareness and appreciation of quality design than to offer them the very’ best buildings in the one area of life that seems to touch them most? Could it even be drat better stadiums might just make tor better citizens?

B

But then maybe, as my detractors have labelled me in the past, 1 am a snob. Maybe I should just accept that sport, and its associated accoutrements and products, is an essentially tacky and ephemeral business, while stadium design is all too often driven by pragmatists and penny-pinchers. Certainly, when 1 first started writing about stadium architecture, one of the first and most uncomfortable truths 1 had to confront was that some of the mast popular stadiums in the world were also amongst the the least attractive or innovative in architectural terms. ‘Worthy and predictable’ has usually won more votes than ’daring and different’. Old Trafford football ground in Manchester, the Yankee Stadium in New York, Ellis Park in Johannesburg. The list is long and is not intended to suggest that these are necessarily poor buildings. Rather, that each has derived its reputation more from the events that it has staged, from its associations, than from the actual form it takes. Equally, those stadiums whose forms have been revered – such as the Maracana in Rio, oi the San Siro in Milan – have turned out to be rather poorly designed in several respects, once one analyses them not as icons but as functioning ‘public assembly facilities’ (to use the current jargon). Finding the balance between beauty and practicality has never been easy.

C

Homebush Bay was the site of the main Olympic Games complex for the Sydney Olympics of 2000. To put it politely, 1 am no great admirer of the Olympics as an event, or, rather, of the insane pressures its past bidding procedures have placed upon candidate cities. Nor, as a spectator, do 1 much enjoy the bloated Games programme and the consequent demands this places upon the designers of stadiums. Yet in my calmer moments ir would be churlish to deny that, if approached sensibly and imaginatively, the opportunity to stage the Games can yield enormous benefits in the long term (as well they should, considering the expenditure involved), if not (or sport then at least for the cause of urban regeneration. Following in Barcelona’s footsteps, Sydney undoubtedly set about its urban regeneration in a wholly impressive way. To an outsider, the 760-hectare sire at Homebush Bay, once the home of an abattoir, a racecourse, a brickworks and light industrial units, seemed miles from anywhere – it was actually fifteen kilometres from the centre of Sydney and pretty much in the heart of the city’s extensive conurbation. Some £1.3 billion worth of construction and reclamation was commissioned, all of it, crucially, with an eye to post- Olympic usage- Strict guidelines, studiously monitore by Greenpeace, ensured that the 2000 Games would be the most environmentally friendly ever. What’s more, much of the work was good-looking, distinctive and lively. ‘That’s a reflection of the Australian spirit,’ I was told.

D

At the centre of Homebush lay the main venue for the Olympics, Stadium Australia. It was funded by means of a BOOT (Budd, Own, Operate and Transfer) contract, which meant that the Stadium Australia consortium, led by the contractors Multiplex and the financiers Hambros, bore i he bulk of the construction costs, in return for which it was allowed to operate the facility for thirty years, and thus, it hopes, recoup its outlay, before handing the whole building over to the New South Wales government in the year 2030.

E

Stadium Australia was the most environmentally friendly Olympic stadium ever built. Every single product and material used had to meet strict guidelines, even if it turned our to he more expensive. All the timber was either recycled or derived from renewable sources. In order to reduce energy’ costs, the design allowed for natural lighting in as many public areas as possible, supplemented by solar-powered units. Rainwater collected from the roof ran off into storage- ranks, where it could be tapped for pitch irrigation. Stormwater run-off was collected for toilet flushing. Wherever possible, passive ventilation was used instead of mechanical air- conditioning. Even the steel and concrete from the two end stands due to be demolished at the end of the Olympics was to be recycled. Furthermore, no private cars were allowed on the Homebush site. Instead, every spectator was to arrive by public transport, and quite right too. If ever there was a stadium to persuade a sceptic like myself that the Olympic Games do, after all, have a useful function in at least setting design and planning trends, this was the one. 1 was, and still am, I freely confess, quite knocked out by Stadium Australia.

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 2?

READING PASSAGE 3

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 27-40 which are base on Reading passage 3

A Theory of Shopping

For a one-year period I attempted to conduct an ethnography of shopping on and around a street in North London. This was carried out in association with Alison Clarke. I say ‘attempted’ because, given the absence of community and the intensely private nature of London households, this could not be an ethnography in the conventional sense. Nevertheless, through conversation, being present in the home and accompanying householders during their shopping, I tried to reach an understanding of the nature of shopping through greater or lesser exposure to 76 households.

My part of the ethnography concentrated upon shopping itself. Alison Clarke has since been working with the same households, but focusing upon other forms of provisioning such as the use of catalogues (see Clarke 1997). We generally first met these households together, but most of the material that is used within this particular essay derived from my own subsequent fieldwork. Following the completion of this essay, and a study of some related shopping centres, we hope to write a more general ethnography of provisioning. This will also examine other issues, such as the nature of community and the implications for retail and for the wider political economy. None of this, however, forms part of the present essay, which is primarily concerned with establishing the cosmological foundations of shopping.

To state that a household has been included within the study is to gloss over a wide diversity of degrees of involvement. The minimum requirement is simply that a householder has agreed to be interviewed about their shopping, which would include the local shopping parade, shopping centres and supermarkets. At the other extreme are families that we have come to know well during the course of the year. Interaction would include formal interviews, and a less formal presence within their homes, usually with a cup of tea. It also meant accompanying them on one or several ‘events’, which might comprise shopping trips or participation in activities associated with the area of Clarke’s study, such as the meeting of a group supplying products for the home.

In analysing and writing up the experience of an ethnography of shopping in North London, I am led in two opposed directions. The tradition of anthropological relativism leads to an emphasis upon difference, and there are many ways in which shopping can help us elucidate differences. For example, there are differences in the experience of shopping based on gender, age, ethnicity and class. There are also differences based on the various genres of shopping experience, from a mall to a corner shop. By contrast, there is the tradition of anthropological generalisation about ‘peoples’ and comparative theory. This leads to the question as to whether there are any fundamental aspects of shopping which suggest a robust normativity that comes through the research and is not entirely dissipated by relativism. In this essay I want to emphasize the latter approach and argue that if not all, then most acts of shopping on this street exhibit a normative form which needs to be addressed. In the later discussion of the discourse of shopping I will defend the possibility that such a heterogenous group of households could be fairly represented by a series of homogenous cultural practices.

The theory that I will propose is certainly at odds with most of the literature on this topic. My premise, unlike that of most studies of consumption, whether they arise from economists, business studies or cultural studies, is that for most households in this street the act of shopping was hardly ever directed towards the person who was doing the shopping. Shopping is therefore not best understood as an individualistic or individualising act related to the subjectivity of the shopper. Rather, the act of buying goods is mainly directed at two forms of ‘otherness’. The first of these expresses a relationship between the shopper and a particular other individual such as a child or partner, either present in the household, desired or imagined. The second of these is a relationship to a more general goal which transcends any immediate utility and is best understood as cosmological in that it takes the form of neither subject nor object but of the values to which people wish to dedicate themselves.

It never occurred to me at any stage when carrying out the ethnography that I should consider the topic of sacrifice as relevant to this research. In no sense then could the ethnography be regarded as a testing of the ideas presented here. The Literature that seemed most relevant in the initial anaLysis of the London material was that on thrift discussed in chapter 3. The crucial element in opening up the potential of sacrifice for understanding shopping came through reading Bataiile. Bataille, however, was merely the catalyst, since I will argue that it is the classic works on sacrifice and, in particular, the foundation to its modern study by Hubert and Mauss (1964) that has become the primary grounds for my interpretation. It is important, however, when reading the following account to note that when I use the word ‘sacrifice’, I only rarely refer to the colLoquial sense of the term as used in the concept of the ‘self-sacrificial’ housewife. Mostly the allusion is to this Literature on ancient sacrifice and the detailed analysis of the complex ritual sequence involved in traditional sacrifice. The metaphorical use of the term may have its place within the subsequent discussion but this is secondary to an argument at the level of structure.

Ielts reading test 3-2

This IELTS Academic Reading post focuses on all the solutions for IELTS Cambridge 10 Reading Test 3 Passage 2 which is entitled ‘Autumn Leaves’. This is a solution post for candidates who have big difficulties in finding Reading Answers. This post can guide you perfectly to understand every Reading answer easily. Finding IELTS Reading answers is a gradual process and I hope this post can help you in this respect.

CAMBRIDGE IELTS 10

Reading Passage 2:

The headline of the passage: Autumn Leaves

Questions 14-18 (Identifying information):

[This question asks you to find information from the passage and write the number of the paragraph (A, B, C or D … .. ) in the answer sheet. Now, if the question is given in the very first part of the question set, I’d request you not to answer them. It’s mainly because this question will not follow any sequence, and so it will surely kill your time. Rather, you should answer all the other questions first. For this passage, first answer question 4- 13. After finishing with these questions, come to question 1-3. And just like List of Headings, only read the first two lines or last two lines of the expected paragraph initially. If you find the answers, you need not read the middle part. If you don’t find answers yet, you can skim the middle part of the paragraph. Keywords will be a useful matter here.]

Question 14: a description of the substance responsible for the red colouration of leaves.

Keywords for this question: substance, responsible, red colouration, leaves

For this question we need to find the clue (the substance) which causes the leaves to turn red. Take a look at the first lines of paragraph C. The writer says, “The source of the red is widely known: it is created by anthocyanins, water-soulable plant pigments reflecting the red to blue range of the visible spectrum.”

This means the substance which is responsible for red colouration of leaves is anthocyanins.

So, the answer is: C

Question 15: the reason why trees drop their leaves in the autumn.

Keywords for this question: reason, trees drop, leaves, autumn

In paragraph B lines 3-7 say, “As fall approaches in the northern hemisphere, the amount of solar energy available declines considerably. For many trees – evergreen conifers being an exception – the best strategy is to abandon photosynthesis until the spring. So rather than maintaining the now redundant leaves throughout the winter, the tree saves its precious resources and discards them.”

So, the lines suggest that many trees like the conifers cannot create photosynthesis due to the lack of solar energy. So, they stop their photosynthesis until spring. The tree drops the leaves to save its precious energy.

Here, discards = drops

So, the answer is: B

Question 16: some evidence to confirm a theory about the purpose of the red leaves

Keywords for this question: evidence, confirm, theory, purpose, red leaves.

In paragraph H the writer starts by saying, “Even if you had never suspected that this is what was going on when leaves turn red, there are clues out there.” The lines suggest that there are some clues or evidences which can confirm the purpose of red leaves. Then, in the following lines the writer shows three evidences to confirm the theory.

So, the answer is: H

Question 17: an explanation of the function of chlorophyll

Keywords for this question: function, chlorophyll

In paragraph B, the author says in the very first lines, “Summer leaves are green because they are full of chlorophyll, the molecule that captures sunlight and converts that energy into new building materials for the tree.”

So, this line explains what chlorophyll does.

So, the answer is: B

Question 18: a suggestion that the red colouration in leaves could serve as a warning signal

Keywords for this question: red colouration, could serve as, warning signal

In paragraph E the first lines talk about a suggestion, “It has also been proposed that trees may produce vivid red colours to convince herbivorous insects that they are healthy and robust and would be easily able to mount chemical defenses against infestation.”

So, this proposal means that the red colouration works as a warning sign for herbivorous insects and protect the trees from those insects.

So, the answer is: E

Questions 19-22 (Completing sentences with NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS):

[In this type of question, candidates are asked to write no more than three words to complete sentences on the given topic. For this type of question, first, skim the passage to find the keywords in the paragraph concerned with the answer, and then scan to find the exact word/words.]

Question 19: The most vividly coloured red leaves are found on the side of the tree facing the _________.

Keywords for this question: most vividly coloured red leaves, found, side, facing

In paragraph H lines 2-3, the writer says,“One is straightforward: on many trees, the leaves that are the reddest are those on the side of the tree which gets most sun.”

Here, the leaves that are the reddest = most viv >

So, the answer is: sun

Question 20: The __________ surfaces of leaves contain the most red pigment.

Keywords for this question: surface, contains, most red pigment

Take a look at lines 3-4 in paragraph H, where the writer says, “Not only that, but the red is brighter on the upper side of the leaf.” Here, the lines mean that the red colour/ pigment is found most (the red is brighter) on the upper side (surface).

So, the answer is: upper

Question 21: Red leaves are most abundant when daytime weather conditions are ________ and sunny.

Keywords for this question: most abundant, daytime weather, sunny

Again, in paragraph H, the writer mentions in lines 4-5, “It has also been recognised for decades that the best conditions for intense red colours are dry, sunny days and . . … . . ” The lines suggest that ‘intense red colour’ (Red leaves are most abundant) when the daytime weather is dry and sunny.

So, the answer is: dry

Question 22: The intensity of the red colour of leaves increases as you go further __________.

Keywords for this question: intensity of red colour, increases, go further

In paragraph H lines 7-8, the writer says, “And finally, trees such as maples usually get much redder the more north you travel in the northern hemisphere.”

Here, the lines mean if you travel further north, you will see much redder leaves / the intensity of red colour will increase.

So, the answer is: north

Question 23-25: TRUE, FALSE, NOT GIVEN

In this type of question, candidates are asked to find out whether:

The statement in the question matches with the account in the text- TRUE

The statement in the question contradicts with the account in the text- FALSE

The statement in the question has no clear connection with the account in the text- NOT GIVEN

[For this type of question, you can divide each statement into three independent pieces and make your way through with the answer.]

Question 23: It is likely that the red pigments help to protect the leaf from freezing temperatures.

Keywords for this answer: red pigments, protect, freezing temperatures

In paragraph D, the writer talks about the possibility of the defense mechanism of red pigments in the very first sentence, “Some theories about anthocyanins have argued that they might act as a chemical defense against attacks by insects or fungi, or that they might attract fruit-eating birds or increase a leafs tolerance to freezing.”

The statement suggests that red pigment actually increases leaf’s tolerance to freezing, not protect the leaf from freezing temperature.

So, the answer is: FALSE

Question 24: The ‘light screen’ hypothesis would initially seem to contradict what is known about chlorophyll.

Keywords for this answer: light screen hypothesis, seem to contradict, about chlorophyll

In paragraph F, the author mentions in lines 1-3, “Perhaps the most plausible suggestion as to why leaves would go to the trouble of making anthocyanins when they’re busy packing up for the winter is the theory known as the ‘light screen’ hypothesis. It sounds paradoxical, … …”

Here, paradoxical = seems to contradict

So, the answer is: TRUE

Question 25: Leaves which turn colours other than red are more likely to be damaged by sunlight.

Keywords for this answer: turn colours other than red, more likely, damaged, sunlight

In paragraph I we find the writer’s confused tone over the issue of colouration of leaves by some trees and not by some others. “…. .. is why some trees resort to producing red pigments while others don’t bother, and simply reveal their orange or yellow hues. Do these trees have other means at their disposal to prevent overexposure to light in autumn? … .. ..”

There is no clue or a clear decision regarding this.

So, the answer is: NOT GIVEN

Question 26: Multiple choice question

For which of the following questions does the writer offer an explanation?

A why conifers remain green in winter

B how leaves turn orange and yellow in autumn

C how herbivorous insects choose which trees to lay their eggs in

D why anthocyanins are restricted to certain trees

In paragraph B we find a clear explanation about how leaves turn orange and yellow in autumn. The writer concludes the paragraph by saying, “.. ..This unmasking explains the autumn colours of yellow and orange. .. . . .. . …”

IELTS Academic Reading test 2 Section 3

This free IELTS reading test (Academic Module) has the same question types, content style, length and difficulty as a standard IELTS test. To get started simply scroll down to read the texts and answer the questions.

Section 3:

The dawn of culture

In every society, culturally unique ways of thinking about the world unite people in their behaviour. Anthropologists often refer to the body of ideas that people share as ideology. Ideology can be broken down into at least three specific categories: beliefs, values and ideals. People’s beliefs give them an understanding of how the world works and how they should respond to the actions of others and their environments. Particular beliefs often tie in closely with the daily concerns of domestic life, such as making a living, health and sickness, happiness and sadness, interpersonal relationships, and death. People’s values tell them the differences between right and wrong or good and bad. Ideals serve as models for what people hope to achieve in life.

There are two accepted systems of belief. Some rely on religion, even the supernatural (things beyond the natural world), to shape their values and ideals and to influence their behaviour. Others base their beliefs on observations of the natural world, a practice anthropologists commonly refer to as secularism.

In larger, agricultural societies, religion has long been a means of asking for bountiful harvests, a source of power for rulers, or an inspiration to go to war. In early civilised societies, religious visionaries became leaders because people believed those leaders could communicate with the supernatural to control the fate of a civilization. This became their greatest source of power, and people often regarded leaders as actual gods. For example, in the great civilisation of the Aztec, which flourished in what is now Mexico in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, rulers claimed privileged association with a powerful god that was said to require human blood to ensure that the sun would rise and set each day. Aztec rulers thus inspired great awe by regularly conducting human sacrifices. They also conspicuously displayed their vast power as wealth in luxury goods, such as fine jewels, clothing and palaces. Rulers obtained their wealth from the great numbers of craftspeople, traders and warriors under their control.

Religion in its more extreme form allows people to know about and ‘communicate’ with supernatural beings, such as animal spirits, gods, and spirits of the dead. Small tribal societies believe that plants and animals, as well as people, can have souls or spirits that can take on different forms to help or harm people. Anthropologists refer to this kind of religious belief as animism, with believers often led by shamans. As religious specialists, shamans have special access to the spirit world, and are said to be able to receive stories from supernatural beings and later recite them to others or act them out in dramatic rituals.

Rapid changes in technology in the last several decades have changed the nature of culture and cultural exchange. People around the world can make economic transactions and transmit information to each other almost instantaneously through the use of computers and satellite communications. Governments and corporations have gained vast amounts of political power through military might and economic influence. Corporations have also created a form of global culture based on worldwide commercial markets. As a result, local culture and social structure are now shaped by large and powerful commercial interests in ways that earlier anthropologists could not have imagined. Early anthropologists thought of societies and their cultures as fully independent systems, but today, many nations are multicultural societies, composed of numerous smaller subcultures. Cultures also cross national boundaries. For instance, people around the world now know a variety of English words and have contact with American cultural exports such as brand-name clothing and technological products, films and music, and mass-produced foods.

In addition, many people have come to believe in the fundamental nature of human rights and free will. These beliefs grew out of people’s increasing ability to control the natural world through science and rationalism, and though religious beliefs continue to change to affirm or accommodate these other dominant beliefs, sometimes the two are at odds with each other. For instance, many religious people have difficulty reconciling their belief in a supreme spiritual force with the theory of natural evolution, which requires no belief in the supernatural. As a result, societies in which many people do not practice any religion, such as China, may be known as secular societies. However, no society is entirely secular.

Questions 23 – 40

Questions 23 – 29

Do the following statements agree with the opinion of the writer? Write

YES if the statement agrees with the writer

NO if the statement does not agree with the writer

NOT GIVEN if there is no information about this in the passage.

- People from all around the world are united by the way they think about culture.

- Our ‘values’ are the most important aspect of >

- Secularism is the most w >

- Shamans act as intermediaries between spirits and the living.

- Agricultural societies benefited from religion.

- In Aztec civilisation, fighters, craftspeople and traders demanded blood sacrifices from the rich.

- In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, European people began turning towards science.

Questions 30 – 34

Complete the summary of the reading text using words from the box.

| belief | latter | religion | faith | ascendancy |

| former | rational | decline | secular | shaman |

There are two main (30) systems which can contribute to our > can be sa > and scientific direction. One reason that explains the (33) of more secular beliefs is the importance given to other factors, such as free will and capitalism. Nonetheless, (34) remains at least to some degree even in the most secular of societies.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

Questions 35 – 40

Answer the questions below using NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS.

- What are beliefs, values and >

- What was sa >

- In Europe, what title was given to the advance of science and logic?

- What two things influenced the development of capitalism?

- Before modern advances in technology, what d >

- What theory is symbolic of the tensions between religion and science?

[the_ad > Show answers

23.NO

24.Not given

25.Not given

26.Yes

27.Not given

28.No (it was the wealthy and privileged that called for sacrifice, not the fighters, craftspeople and traders)

29.Yes

30.Belief

31.Former

32.Rational

33.Ascendancy

34.Religion

35.Ideology

36.Human sacrifice OR human blood

37.Age of Enlightenment

38.Religion and science

39.Fully independent systems